The Cane Toad Problem

The Cane Toad (Rhinella marina) has become an all-too-familiar species across the northern parts of Australia. These troublesome pests have managed to work their way across northern Australia and have been a major threat to our biodiversity since Day 1. But why are they such an issue? How have they spread so far? And what’s being done to help solve the Cane Toad problem? Let’s have a look!

An adult Cane Toad, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-02-05/cane-toads-protecting-turtles-goannas-wreck-beach/9396136

Cane Toads are one of the largest toad species in the world. Although females normally only reach around the 12cm mark, the largest can get to over 20cm and weigh over 800g! That’s one massive amphibian! These big, tough toads originate from Central and South America, where they occupy a large range of habitats, from open grasslands, to forests, to urban backyards. This is also an old species; fossils found in Colombia from the late Miocene (a period which ended ~5.33 million years ago) are almost identical to modern day toads. They will eat anything that fits in their mouth, and although this usually means invertebrates, they will also prey on small reptiles, rodents, birds and even bats! Whilst they hunt by detecting movement, they also have a great sense of smell, and will eat things like dog food and plants too.

Natural range of Rhinella marina, https://www.canetoadsinoz.com/invasion.html

Now why take a big, tough survivor of a species like the Cane Toad, and move it to Australia? Well, the species was introduced to QLD in 1935 to help deal with a plague. The grey-backed cane beetle (Dermolepida albohirtum) and Frenchi beetle (Lepidiota frenchi), two native beetle species, were really tucking into the sugar cane crops and something needed to be done. As the chemicals used back then to control such pests were VERY nasty, the toads were seen as a safer alternative. It was hoped that the toads would eat the beetles when they came to the ground to breed, but there is no proof that this was ever successful. Regardless, with very few natural predators and a huge range of resources, the introduced toads quickly exploded in numbers and began to spread across northern Australia. Nowadays, they have spread from QLD down to northern NSW, and have crossed NT into northern WA as well.

There are three main reasons why the Cane Toad has become such a successful invader of our native landscape:

1: Cane Toads are TOUGH.

Big and bulky, and able to tolerate a range of habitats and conditions, the open spaces of northern Australia are just about perfect for the Cane Toads. As long as they have access to water for breeding, and can at least absorb morning dew for a drink, they’re pretty comfortable. Also, those huge lumps on the back of their head? Those glands pump out a toxin that is lethal to almost all of our native predators. They have caused many northern carnivores to drop in number, including Yellow Spotted Monitors (Varanus panoptes), Mertens’ Water Monitors (Varanus mertensi), and Northern Quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus).

2: Cane Toads spread FAST.

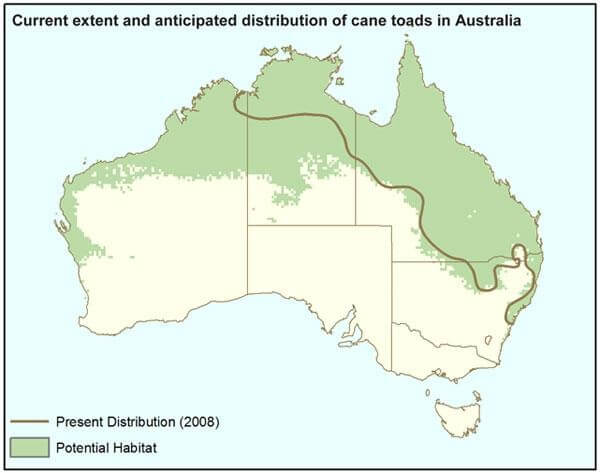

Since their release into QLD in 1935, they have managed to spread west at about 10km per year to begin with – but that has now increased to between 40 and 60km per year! Being surrounded by unoccupied toad territory full of food, toads at the front line of the spread have evolved to be faster – the faster toads get the resources quicker, breed, and their offspring have the same advantages. The map below shows roughly where the toads were back in 2008, and the estimated total occupancy area:

Source: Kearney, M, Phillips, BL, Tracy, CR, Christian, KA, Betts, G & Porter, WP 2008, ‘Modelling species distributions without using species distributions: the cane toad in Australia under current and future climates’, Ecography, vol. 31, pp. 423–434.

This map, however, is 10 years old. By 2010 there was a report of a Cane Toad in Broome.

3: Cane Toads breed like CRAZY

Cane toads are breeding machines. They may only breed once a year, but when they do, they do it on a huge scale. One female can put out a whopping 30,000 eggs in one breeding effort. In just a few days 30,000 tadpoles hatch from those eggs and considering how toxic the tadpoles are too, there’s not many predators lowering those numbers – in fact, the number one predator of cane toad eggs are cane toad tadpoles! They absolutely LOVE to munch on the their own species throughout most of their life cycle!

A single clutch of Cane Toad eggs – https://www.canetoadsinoz.com/cane_toad_biology.html

So these toads are big, tough, toxic, voracious consumers, and spreading rapidly. How can we possibly stop them? In recent times, there have been several interesting discoveries that may aid in the quest to bring this pest under control.

Seeing as the toads can have such large numbers of offspring, if we could control them at the tadpole stage before they even emerged from the water, it’d be a great way to stop them spreading over land. And several chemicals produced by the tadpoles themselves may help that happen. The first is that the tadpoles will release an ‘alarm pheromone’ when stressed, and this causes any tadpoles in the area to flee from whatever the immediate threat might be. By adding this chemical to water sources with Cane Toad tadpoles in them, it was found that the stress alone killed around 50% of the tadpoles. Not only that, but when the baby toads emerged from the water, they were much smaller and weaker than those that weren’t exposed to the chemical. On top of the toad tadpole’s reaction to the presence of the pheromone, it was also shown that native frogs and tadpoles don’t even seem to notice its presence, which is beneficial as it means we don’t risk our native species by using it.

So we can drive the tadpoles away, but what about attracting them? Another recent discovery was a chemical that draws in Cane Toad tadpoles, but again is completely ignored by their native counterparts. When used to trap tadpoles, it was shown to be useful in completely eradicating the tadpoles from testing ponds! How amazing is that? Plus, even more recently, a chemical has been found that causes the older tadpoles to attack and kill the younger ones! A little bit of chemistry may be a great way to fight the toads before they even leave the water.

It’s no secret that fighting the Cane Toad is an uphill battle, but that battle is not over and with some seriously good leads on the chemical front, hopefully we can see some broader control trials in the not-too-distant future!