Going Batty!

The story of a very misunderstood species

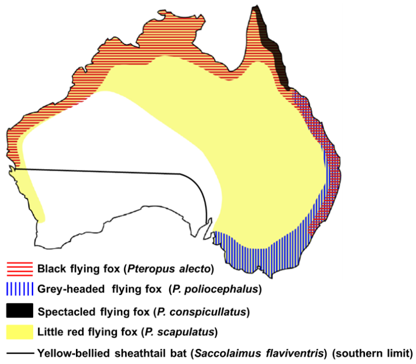

Bats get a bad rap. Often painted as ‘night-flying, beady-eyed, leather-winged, blood-sucking, disease-carrying, smelly, dirty vermin’, the nightmare creatures of horror movies and urban myths couldn’t be further from the truth. Australia is home to 77 species of bat, with most of these being microbats; small, mostly insectivorous bats that use echolocation to catch invertebrates on the wing. However, 4 of our mainland Australian species belong to the genus Pteropus, or as they are more commonly known, the Flying-foxes. These large, fruit-eating flying mammals are normally associated with the more tropical zones, but one species has managed to spread all the way down the east coast and throughout most of southern Victoria – and it’s the largest species of bat in the country.

Introducing the Grey-headed flying-fox!

One of Reptile Encounters’ Grey-headed flying-foxes. Photo by Volunteer Sarah Bright

Weighing up to a kilo and a one metre wingspan, these huge nocturnal fruit-eaters look very much like large crows flying overhead in the dark of night, unless you get a good look at the shape of their wings. The name Flying-fox comes from their fox-like faces, but these megabats are not related to canines – in actual fact, they are far more closely related to primates – like monkeys, apes, and us! Grey-headed flying-foxes are very vocal, able to make a complex series of squeals and screeches. They will flap their wings in hot weather, using blood pumped through the patagium to cool the body temperature.

The Grey-headed flying-fox is long-lived for a mammal of its size. Individuals reportedly survived in captivity for up to 23 years, and a maximum age of up to 15 years seems possible in the wild.

During the day, individuals reside in large roosts (colonies or ‘camps’) consisting of hundreds to tens of thousands of individuals. Camps will form in a range of locations and the population of each camp can vary greatly depending on season and food availability.

Pollen, nectar and fruit makes up the bulk of the diet of this species. 187 plant species have been recorded as being used for food by Grey-headed flying-foxes. The bats will chew up their food, swallowing down the juices before spitting out all the unwanted fibrous material. Due to their food trees blossoming seasonally and unpredictably, Grey-headed flying-foxes have been recorded flying up to 50km in a single night just to reach flowering or fruiting trees.

One of our captive Flying-foxes enjoying the nectar from a native bottlebrush flower. Photo by Volunteer Sarah Bright.

Grey-headed flying-foxes live in a variety of habitats, including rainforests, woodlands, and swamps.Their ‘camps’ are variable in size and move seasonally; in the warmer parts of the year they will roost in cool and wet gullies in large groups. Roost vegetation includes rainforest patches, stands of melaleuca, mangroves, and waterside vegetation, but roosts also occupy highly modified vegetation in urban areas.

A Bat In Trouble

There are reports from many decades ago of Grey-headed flying-fox camps of up to one million bats. There are also reports of a new camp every 40 kilometres or so. These kinds of numbers would have been absolutely mind-blowing to observe blackening the evening skies on their nightly voyage to fill their bellies with sweet things, but sadly these days are long behind us.

The National Grey-headed flying-fox population may have dropped by over 30% between 1989 and 1999 alone, and was estimated to be 680,000 (±164,500) in 2015. That said, the numbers aren’t completely certain (hence the huge margin of error). There’s two main reasons for this:

• The species is incredibly mobile, with individuals recorded making round trips of up to 2000km

• Not all current roosting sites being used are known. Camps can fluctuate massively over the course of the year, with camps of only 1,000 bats suddenly swelling to tens of thousands during certain times of the year, and some camps being suddenly abandoned and not used again for years.

According to the ‘State Wide Integrated Flora and Fauna Teams’, or ‘SWIFFT’, there are at least 11 Grey-headed flying-fox camps in Victoria, 8 of these being in East Gippsland which also has the largest permanent and birthing camp at Dowell Creek near Mallacoota. The following table lists all known camps in recent history, including some of the temporary camps that only occur at certain times of the year, and the rough populations of each at peak season:

Site | Numbers (in summer) | Details |

Upper Maffra | Used in 2004 by 5000 - 10,000 individuals | Appeared when local Ironbarks were in flower |

Yarra Bend | Up to 30,000-50,000, second largest in Vic | Year-round occupation and breeding |

Eastern Park, Geelong | Up to 18,000, usually 5,000 | Year-round occupation and breeding |

Merrimu (Moorabool) | Not known | Needs monitoring |

Bacchus Marsh | Not known | First noted in 2019 |

Rosalind Park, Bendigo | Peaked at 32,000 in 2010 | Mostly present here in winter, with numbers having dropped significantly |

Colac | 4,000 | Has been increasing since 2016 |

Bairnsdale | Up to 10,000, usually only 5,000 | Usually occupied from December-May |

Cabbage Tree Creek | Several thousand at one site up until 2003, 10,000 at another site | 2 camps here but one has been abandoned for many years. |

Cann River | No longer in use | Abandoned since 2002 |

Dowell Creek | Largest colony in Victoria | Year-round occupation and breeding |

Karbethong | 90,000 in 2003, much smaller numbers since. | Large fluctuations in the size of this camp |

Newmerella | 10,000 in 2002 | After a large camp was established in 2002, it was then completely abandoned until 2008. |

The Grey-headed Flying-fox has been in decline since the 1920’s. Habitat loss is a serious issue, with clearing of forested areas for agriculture being linked as a major factor in the species’ decline. Between 1992-2002, it is estimated that there was a 35% decline in the total number of bats, which is a massive loss and had them named as a threatened species. This loss of roosting sites and foraging areas led to the bats beginning to raid fruit orchards for food, where clashes with humans have occurred, and very rarely do the bats come out on top. Shooting and poisoning, both legally and illegally, have had a massive impact on the bats, with an estimated 240,000 individuals estimated to have been culled in Sydney and QLD between 1986-1992 – luckily, the species is protected from culling in Vic. Electrocution from bats landing on power lines also causes a significant number of deaths each year, with dead bats a not-so-uncommon sight hanging from the wires the day after. Grey-headed flying foxes can also become tangled and injured by bird netting over fruit trees, or barbed wire fences, which can result in injury or death. Finally, weather and climate also have a huge impact on the species as well, with large numbers literally ‘dropping out of the trees’ during heat waves.

Grey-headed flying-fox camp on the Hawkesbury River, NSW. Photo: https://www.hawkesburygazette.com.au/story/6457488/steer-clear-of-flying-fox-colony/

V.I.S.P.: Very Important Sky Puppies

Bats are incredibly important worldwide. Most microbat species consume insects, including serious agricultural pests and disease vectors such as mosquitoes – some bat species can consume 1000 insects an hour. In fact, in the US alone it’s estimated that bats are worth more than $3.7 BILLION dollars annually just in crop damage prevention, and the terrific job they do also means less need for pesticides, which can be incredibly damaging to any ecosystem they enter.

Flying-foxes, on the other hand, have an even more important job – pollination and seed dispersal. The Grey-headed flying-fox is the only nectivore and frugivore known to inhabit substantial sections of subtropical rainforest, making it even more important to the ongoing health of our forests. A whopping 187 species of native plants are consumed by the Grey-headed flying-fox, including many species of eucalypts and fruiting rainforest species such as figs. Unlike other pollinators such as bees, moths, and butterflies, flying-foxes can spread pollen over much larger areas. Even many of the nectivorous bird species, such as honeyeaters, won’t risk leaving the dense vegetation out of fear of being exposed to predators. Flying-foxes can travel up to 50km a night from their camps to feeding areas, and so they have the ability to spread plant genetics over a far larger area than other pollinators.

Seed dispersal is also a critically important job in any ecosystem, and there aren’t any other animals that do it as well as flying-foxes. Again, with the long journeys the bats undertake each night, they’ll be going to the toilet over quite a large area! This means that the plant species they’re feeding upon can have their seeds spread far and wide. Because of this, the Grey-headed flying-fox is considered vitally important in the regeneration of forests after events such as land clearing or bushfires – and with the catastrophic bushfires across eastern Australia over the 2019-2020 summer, the role the Grey-headed flying-fox plays is more important than ever. This is particularly important here in Victoria, where the Grey-headed is by far the dominant bat species represented in the state, and the only one permanently present here. The only other species that is sighted this far south is the Little red flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus), a smaller and far more nomadic species. Little reds only venture into northern Victoria depending on food availability, and are considered a semi-permanent resident of the state. They are also almost exclusively nectarivores, having evolved a brush-like tongue similar to honey-eaters and lorikeets. This makes them fantastic pollinators, but as they don’t eat much fruit, they are not as prominent a seed-dispersing species as our resident Grey-headed flying-foxes.

A large colony of flying-foxes leaving the roost to disperse and forage in late afternoon/evening is a spectacular sight to behold. Photo: https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6076610/flying-fox-mystery-drives-experts-batty/

Bats of Melbourne

Until the 1980s, Grey-headed flying-foxes were only a very occasional visitor to the Melbourne area, rarely making it this far south. With Melbourne’s average temperature increasing by 1.13°C over the last 20 years, and with fewer frosts, it became easier for a tropical species to set up this far south. The southern spread of another species, the Black Flying-fox (Pteropus alecto), which outcompetes the Grey-headed in many areas where their ranges overlap, and this would have contributed to the species moving south as well. Over the winter of 1986, a few individuals moved to the Royal Botanical Gardens and over the next decade and a half this grew into the enormous colony we have in Melbourne today. Due to the increasing vegetation damage at the Gardens, the colony was relocated in 2003 to Yarra Bend Park, a park covering 260 hectares with over half being beautiful native bushland; the perfect home for the colony.

Are Bats a Threat to Our Health?

As we mentioned at the beginning of this article, bats get a bad rap for being disease-spreading blood-sucking horror creatures. So let’s put some of these myths to bed, starting with the biggest of all.

Australian. Bats. Do. Not. Carry. Rabies!

Rabies is a type of virus known as a lyssavirus, and does not occur in Australia. At all. We do not have rabies in Australia. Therefore, our bat species do not have rabies.

What we DO have here in Australia is Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV). It is another member of the lyssavirus family, and although related to rabies it is not the same disease. ABLV is fatal to humans if infected, and has no known cure.. Being a zoonotic disease (zoonotic meaning that it can pass from animals to humans), humans can catch it directly from bats that carry the disease. ABLV was first discovered in 1996, and since then we’ve learned a few things:

• ABLV has been found in all 4 mainland species of Australian flying-foxes, as well as one insectivorous species, the Yellow-bellied Sheath-tailed bat (Saccolaimus flaviventris)

• There is evidence that the disease has existed in other Australian bat species in the past, so for safety we presume that any wild bat could potentially be carrying ABLV

• An EXTREMELY small percentage of wild bats carry ABLV. In fact, in the 5 species we know are regular carriers of the disease, it’s less than 1%. This increases to 7% of sick, injured or orphaned bats found.

• Of this tiny percentage, only an even smaller percentage actually show symptoms. Many individuals carry the disease with no outward signs of infection

• Since its discovery in 1996, ABLV has been responsible for 5 (non-bat) confirmed deaths – 3 people and 2 horses.

ABLV is spread through contact with mucous or saliva from infected bats, so avoiding the disease is simple. Do NOT touch wild bats, especially if they are sick or injured. If you find a bat on the ground or hanging low in a tree looking unwell, call your local wildlife carer IMMEDIATELY and monitor the bat from a safe distance. Wildlife carers who work with sick, injured and orphaned bats are vaccinated against ABLV and can safely interact with bats in need.

The current ranges of all 5 species of ABLV-carrying bat species in Australia, including the 4 species of flying-foxes. Picture: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/6/2/909/htm

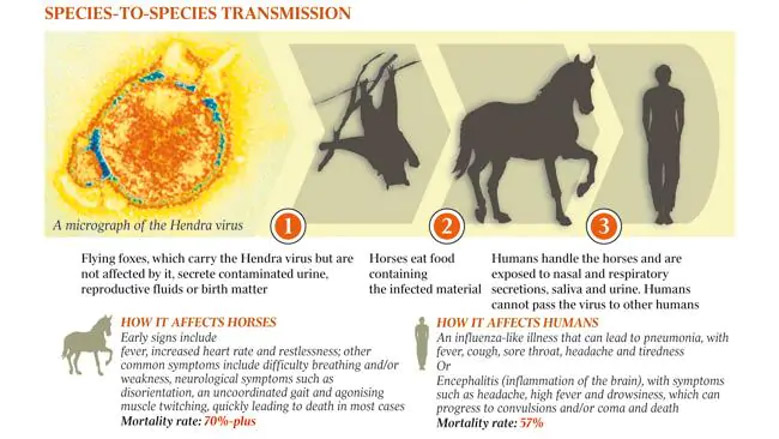

Another zoonotic disease, Hendra Virus (HeV), was discovered in the Brisbane suburb of Hendra in 1994. This member of the henipavirus family is found in all 4 mainland flying-fox species, and this disease works in a slightly more complicated manner; It is not transmitted directly from bats to humans. The disease was discovered, and is most prevalent, in horses. Thought to be passed via contact with saliva, mucous, or bodily fluids of infected bats (although this isn’t completely confirmed), it’s thought that horses contract the disease by eating grass under trees where bats have been foraging, and subsequently ingesting urine/faeces/chewed up fruit left by the bats. There has also been a single case of a dog infected with HeV in 2011. Here’s the facts:

• Hendra virus can only be transmitted to humans via another animal host, and not directly from bats.

• Since its discovery, there have been 7 confirmed cases in humans, 2 in dogs and over 90 cases in horses.

• Of the 7 humans confirmed with the disease, 4 died.

• Several hundred other people have been exposed to the virus during outbreaks, and have not contracted the disease.

• It has a fatality rate of 57% in humans, and 70-75% in horses.

• There has been a vaccination available for horses since 2012.

The best way to prevent becoming infected with HeV is simple; always use appropriate hygiene when working with, or around, animals. Kissing horses on the muzzle brings you into direct contact with a part of the body containing saliva and mucous, and in areas prone to HeV outbreaks seasonally this is NOT a good idea. Not only that, but now that the disease has been shown to infect other animals as well, it is more important than ever to wash your hands after working with animals, and don’t put your hands on your face or in your mouth. This should all be standard procedure with animals regardless, so realistically the chances of becoming infected with HeV are still incredibly low.

Hendravirus can only be spread from bats to humans via an intermediate horse host. It cannot be passed bat-human or human-human. Picture: https://cdn.newsapi.com.au/image/v1/6a9d9ce69a1d5c0c1491edfd7b44aa9d

Recently, there has been increasing fears amongst the public that there is a risk of catching Covid-19 from Australian bats. Now whilst this coronavirus has occupied the headlines, radio waves and media spaces for the majority of 2020 so far, and the global human population are suitably worried about catching the disease, it is important to have a look at the facts.

The Wuhan wet-market hypothesis that someone ate a bat and started a global crisis has been widely spread and some outlets may have you believe it as fact, and whilst the origins of the disease are looking increasingly more likely to be from bats. Yes, the fact that bats naturally run at a hotter temperature than humans does means that our bodies’ fever response won’t kill the virus, but rather makes it stronger, but here’s what we currently know about Covid-19:

• The disease is believed to have evolved naturally (sorry to all those keen on the ‘This diseased was an engineered bio-weapon’ conspiracy theory) and closely resembles similar coronaviruses found in bats and pangolins

• Past coronaviruses have jumped to humans from animal hosts, such as SARS (which came from civets) and MERS (which came from camels)

• There may very well have been another host in between the bat/pangolin and the first human infection, as we have seen with HeV

• The structure of the virus seems to be very similar to coronaviruses infecting pangolins naturally, and so it’s looking pretty likely that the whole pandemic may have started from ingesting one of the most poached animals on the planet (how’s that for karma?)

• If the disease originated in China, why would it suddenly be present in a different species, found thousands of kilometres away? The chances of it jumping from humans back to animals are lower than the chances of the disease jumping to humans in the first place.

Spread Seeds, Not Rabies

So there you have it. Are Flying-foxes winged vermin hell-bent on infecting you, your family, and your favourite pets? Not even close. Are they carriers of rabies, pandemics, and bad credit ratings? Not in the slightest. Are they intelligent, far-travelling pollinators with the ability to regenerate forest at a rate of 60,000 seeds per bat, per night? THERE you go. Flying-foxes, or ‘sky puppies’ as they are affectionately known by those who work closely with them, are incredible creatures vital to the ongoing health of ecosystems across almost the entire eastern side of Australia. They are beautiful, misunderstood creatures who are, to put it simply, trying to find food, avoid predators, and get on with the important ecological duties that they are on this earth to do.

So the next time someone mentions rabies, ‘problem bats’, vermin or ‘Covid-infected demons’, tell them they’re wrong. Spread the love of ‘sky puppies’ to the masses!

A full-grown Grey-headed flying-fox showing off that 1-metre wingspan as he heads out for a night of not spreading rabies or Covid-19. Photo: https://www.pinterest.com.au/pin/238972323951475931/