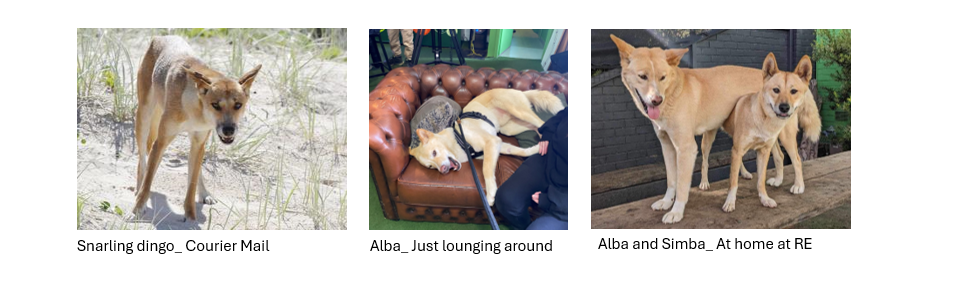

Dingoes are not wild dogs

When left alone in the wild, dingoes are shy.

Can you imagine your dog being killed like this?

We’ve all heard the stories – wild dogs kill livestock and wreak havoc on agriculture and native wildlife alike, so control methods like shooting, leg-hold traps, or 1080 poison baiting feel acceptable and even necessary to some people.

Pest control methods for wild dogs have been widespread in rural areas of Australia since European farming began around 200 years ago.

I would argue that none of these methods are humane.

Traps and baiting are the most common methods. Leg-hold traps can hold an animal in excruciating pain, dying slowing over days.

Then there’s 1080.

This poison is packed into chunks of meat and dispersed across landscapes where pest species are found, with the unfortunate side-effect of killing companion animals and other wildlife if they come across it.

Animals die in fear, with violent convulsions, vomiting, diarrhoea and disorientation.

Witnesses of pet dogs dying this way suffer traumatic grief, but no one is out in a field watching wild dogs die this way, and no one could help them if they did.

Some of these practices are so deeply ingrained that landholders are shamed for not using them.

Conflicting messages abound. On one hand, dingoes are considered native wildlife, and native wildlife are protected under environmental laws, but loopholes exist for pest species on private property. So how do we navigate these conflicting messages? One solution has been to rebrand these natives as pests and call them a generic ‘wild dog’.

The media and public believed that the dingo-looking dogs we saw in outback Australia were hybrids of dingoes and introduced dogs, or purely introduced dogs that escaped into the wild and were now breeding uncontrollably and creating packs of predators terrorising native wildlife and livestock. We believed there were barely any pure dingoes left in the wild.

Then we believed that these wild dogs needed widespread management, aka culling. State Governments list dingoes as ‘wild dogs’, allowing them to be managed as pests. Some even legally require control of wild dogs by landholders.

Can you believe that Victoria has a Wild Dog Bounty program still active at the time of writing, offering monetary rewards for wild dog body parts?

What if those wild dogs were our very own precious dingoes?

A study released in 2023 threw a spanner in the works, revealing that the majority of wild dogs are in fact pure dingoes. So does this change how they are managed? It hasn’t yet, but it should.

The horrific deaths these animals suffer should be enough to stop this practice, but putting the ethical implications of culling any animal aside, dingoes play a vital role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. No one really knows when dingoes arrived here, but it’s expected to be somewhere between 4000 and 7000 years ago, some say up to 18,000 years, more than enough time to integrate into our ecosystem and become a native species.

Australia lacks terrestrial apex predators so their arrival meant that dingo prey like kangaroos and wallabies were kept under control. Keeping grazing herbivore numbers low means vegetation can grow and thrive, forming a vital food source for other herbivores and pollinators, critical shelter and nesting sites for a massive range of other wildlife, air purifiers and can even benefit agriculture.

Without them, we catch ourselves in a vicious cycle of culling the dingoes, then culling the over abundant herbivores and introduced predators like foxes and cats, trying to manually balance ecosystems far beyond the abilities of most humans to manage effectively without causing unintended negative consequences.

So to look at this simply, apex predators are vital in terrestrial ecosystems, dingoes serve this important function, most wild dogs are actually our very own native dingoes, and culling practices are often inhumane.

Fear of human-animal conflict, predation on livestock or pets, and feral dogs overbreeding and running rampant, which ironically happens more when other suitable mates are removed through culling, all create the pressure on Australians and governments to control these populations.

Of course, we don’t advocate befriending wild dingoes, like any animal they can react when provoked or feel threatened.

What would happen if we left them alone?

Seems unimaginable, but some farmers are starting to do this, with promising results. Various graziers with Landholders for Dingoes have experimented with leaving wild dingoes on their property and so far have positive stories to tell.

Dingoes left alone establish pack hierarchies that prevent rogue young males from wreaking havoc on livestock as it’s not needed for their survival and they learn hunting from their older surviving parents, population numbers remain low as they establish a healthy family dynamic and don’t over breed, large herbivores like kangaroos that once overgrazed vegetation have reduced in population to healthy levels, and even introduced pest species like cats, rabbits and foxes have reduced. The result has been a healthy, functioning ecosystem.

Time will tell if this practice sets in as a new social norm. It will also tell if these initial stages continue to show positive results. Given our Traditional Owners lived this way successfully for thousands of years, and many support bringing dingoes back to country, something tells me it just might.

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash