Eastern Barred Bandicoots – It’s Not Over Yet!

You might have heard in the news recently, in amongst the regular madness of the modern world, a success story in Australian conservation. ‘Eastern Barred Bandicoot Back From Brink Of Extinction’, or similar, blazed across newspapers, websites and even the nightly bulletins. But is this the case? Is this marsupial in safer waters now after decades on the verge of disappearing? Let’s take a closer look.

Bandicoots are an amazing group of marsupials. With around 20 species found in Australia and Papua New Guinea, these small to medium sized marsupials inhabit a range of habitats across their range, from tropical rainforests to arid desert regions. Since European settlement, this group (much like many other similar-sized marsupials such as bettongs and potoroos) have not done very well. The large-scale habitat loss, and introduction of feral predators such as foxes and cats, have resulted in many species becoming endangered or extinct. One such species that has clung on by the a thread is the Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunnii).

The Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunnii).

Source: https://10daily.com.au/news/australia/a191011haxmd/nearly-extinct-aussie-bandicoot-given-new-hope-on-new-island-home-20191012

Once common across the western plains and grasslands of Victoria, with a separate subspecies in Tasmania, this little marsupial has been decimated by land clearing and introduced species. With over 90% of Victoria’s native grasslands gone, as well as the constant predation from introduced foxes and feral (and domestic) cats, the bandicoot’s population all but vanished on the mainland, and was reduced to a single population living in, of all places, a garbage tip in Hamilton! The bandicoots were living in old, rusted-out car bodies which provided protection from foxes. How amazing is that?!

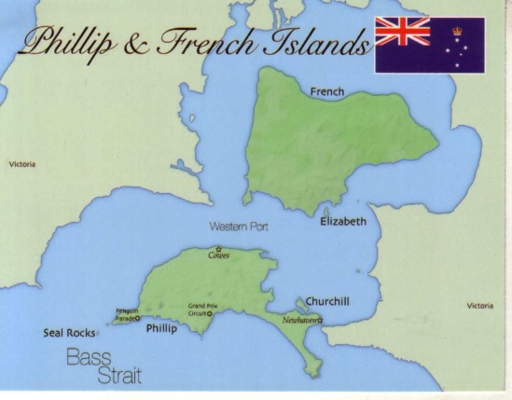

Decades later, and we’re hearing in the news that the species was successfully introduced to Churchill Island in 2015 for a trial, followed by Phillip Island in 2017 and finally French Island last year. Ongoing control measures of foxes and feral cats meant that the islands were relatively free of introduced predators, and a lot of the local wildlife had shown signs of recovery. After the initial releases of 20 bandicoots on Churchill, 67 on Phillip and 55 bandicoots to French Island, the population across the three islands is estimated to have risen to over 500 animals. Not bad, considering the species was down to around 100 individuals of the mainland subspecies.

This is definitely a win. But in no way is this species out of the woods (and back onto the grasslands) yet. Not by a long shot.

One of the main threats to the bandicoots, and many other Australian native species, is the introduced Red Fox (Vulpe vulpes).

Source: DPIW Tasmania, via https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/streetstories/fox-with-bandicoot/3260206

The success of this release program shows exactly how well our native species can recover when foxes and feral cats are controlled. A bulk of this increase in numbers has occurred in just 3 years, and it’s little wonder, with the bandicoots able to breed quite rapidly – females are only pregnant for around 12.5 days, can have up to 5 in a litter, and can give birth to a new litter shortly after the last litter weans at 3 – 5 months of age, and females are ready to breed shortly after weaning. A female can have 5 litters in one breeding season! Now they may only live for 2-3 years in the wild, but with that kind of turn around we should be seeing multiple generations born each breeding season! Just goes to show how much they have been decimated by foxes, cats and land clearing, and with all three of these issues still ever-present on the mainland, what is the next step in getting these guys off of the islands?

Actually, now that we mention it, let’s talk about the islands themselves.

The three islands used for the bandicoot release.

Source: https://postcard.pics-sydney.com.au/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=182_191_183&products_id=927

Churchill Island, French Island and Phillip Island may now very much be the stronghold of mainland Eastern barred bandicoots, but the grasslands found there now were once grazing areas. Before that, the landscape was very different. And, most interestingly, Eastern barred bandicoots did not naturally occur there. In fact, the original habitat type of these islands is much more suited to the also-endangered Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus), which is found nearby on the Mornington Peninsula and may very well have existed on any or all of these islands before settlers changed the landscapes. Now the Southern brown bandicoot has a far larger current distribution, and is actually considered locally common in some areas despite its nationally endangered status, and obviously the mainland Eastern barred bandicoots in much more immediate danger, but the question still stands. Why weren’t the Eastern barred bandicoots released somewhere WITHIN their natural range?

The answer is, that did happen. It just did not go well.

At Gellibrand Hill Park, part of the Woodlands Historic Park just north of Melbourne Airport, a 1.8m high electric fence was built in 1987 to exclude predators from a 400 ha area of grassland and grassy woodland, known as the nature reserve or “back paddock”. This area was never thought to be large enough to establish a genetically viable population, but it was decided that there would be animals swapped between here and the still-barely-surviving natural population that existed at the Hamilton tip (a population that was virtually extinct by 1992). After a single female was released into the predator-proof area in 1988, the total released was at around 88 by April of 1993. By November ‘93, there were an estimated 500 bandicoots in the ‘back paddock’, peaking at over 600 by 1995. This is just as successful numbers-wise as the current project, but actually occurred in the natural range of the species.

But then everything went south.

Despite reports saying that the only way to maintain the habitat for the bandicoots was to make sure kangaroo numbers were kept under control, this just did not happen. It was initially estimated that the kangaroo population (Eastern grey kangaroos, Macropus giganteus, another grassland native) should not have been any larger than 1 per hectare, or 400 in the enclosure. It was well over twice this by 1997 and with a drought affecting the park in 1994, plus over 120 bandicoots being taken to restock other populations, the Woodlands bandicoots were in trouble.

Over the next ten years, a host of issues plagued what was now looking like a lost cause, and eventually releases stopped, as did monitoring. Foxes also seemed to be a continuous problem as well, and high predation occurred at several times in the project’s history. If you’re keen to read more, check out http://whp.altervista.org/bandicoot.php, part of the Woodlands Historic Park website that goes into detail on the bandicoot project. One quote that stands out though, is this: ‘The Recovery Team has no power, no authority, lacks resources and funding’. This came from Peter Myroniuk, a member of said Recovery Team.

An Eastern Barred Bandicoot being released.

Source: Phillip Island Nature Parks Twitter page

Several other fenced-in release sites have been set up, such as at Tiverton in western Victoria, and at Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Interpretation Centre, a privately-owned organisation that relies on tourism. Between these sites, the efforts of Zoos Victoria, and the seemingly-successful releases on Churchill, Phillip and French Islands, we can only hope that the Eastern Barred Bandicoot can one day persist on the western plains of Victoria again. But the only way to see that come true is to do what we as humans struggle to do; learn from past mistakes. Continuous monitoring, funding and fox control is needed, which can help save not only the bandicoots, but a host of other species as well.